Is China already too far ahead with its A2AD strategy, or is it more of a political means to an end?

When Low Observability (LO) to radar, or ‘Stealth’, was first talked about, the concept was widely misunderstood. People thought that stealth rendered aircraft effectively invisible to radar, thereby conferring invulnerability to enemy air defences. The truth was more nuanced, and was always about delaying detection, and about mission planning to avoid the most dangerous threats.

Anti-access/area denial (know widely as A2/AD) has been similarly misunderstood and over-estimated. The complex web of systems developed and deployed in an effort to achieve A2/AD capabilities does not create an impenetrable ‘keep-out zone’, nor does it guarantee the destruction of any enemy system foolish enough to enter an area, it just extends the range and area at which a given part of the battlespace may be judged to be more highly contested.

The term A2/AD is most closely associated with the People’s Republic of China (China), which developed the concept after realising that it had no means of adequately countering or contesting US Navy carrier battle groups, which effectively had enjoyed uncontested access to waters that China viewed as its own. This situation became obvious in July 1995, when the US dispatched two US carrier battle groups to the Republic of China (ROC – Taiwan) after a series of Chinese missile firings and highly publicised amphibious assault exercises, and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) could do nothing to halt it.

China was eager to prevent any future ‘interference’ with what it views as its ‘internal affairs’, and in particular to limit the USA’s ability to respond to Chinese moves against Taiwan. To achieve this, it needed to push US forces further back from China’s coast, and it did this by deploying a raft of new systems, defensive and offensive, all linked via a better integrated command and control system. But this was not just a practical matter of preventing interference over Taiwan. The ability of the US Navy to operate unrestrained in China’s back yard was an affront to China’s national pride, and there was an emotionally-driven desire to be able to push US forces out of the maritime areas surrounded by the Nine Dash Line.

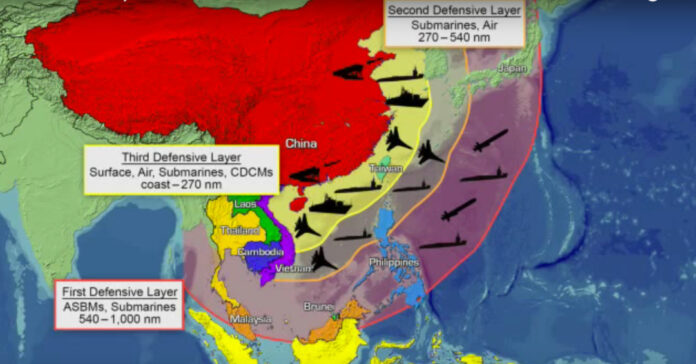

China based its A2/AD concept on the ‘Sea Denial’ or ‘Bastion Strategy’ favoured by the Russians, using very long-range land, air and sea-based precision fire and ballistic missile capabilities to hold enemy force elements at risk over much greater distances.

For anti-access, China relies on advanced land-attack ballistic and cruise missiles such as the DF-26 to threaten US ships, forcing America’s aircraft carriers back to a distance at which the effectiveness of their aircraft would be severely reduced, and forcing back surface ships so far that their Land Attack Cruise Missiles (LACMs) become an irrelevance. The same missiles also threaten military facilities on the vital Pacific islands of Okinawa and Guam. Guam, a base for American strategic bombers such as the Boeing’s B-1, B-2 and B-52, is now considered to be wholly at risk. China’s DF-26 has even been widely labelled as “the Guam killer.”

China’s long-range missiles are supported by a rapidly growing number of space-based sensors, including a constellation of Naval Ocean Surveillance System satellites. These provide persistent coverage of the waters surrounding China and could provide targeting for anti-ship ballistic missiles.

China’s anti-ship and cruise missiles can reach out to beyond the so-called First Island Chain. This string of islands includes the Kuril Islands, the Japanese Archipelago, the Ryukyu Islands (notably Okinawa), Taiwan, and the northern part of the Philippines, effectively enclosing the East China Sea and the South China Sea. In some interpretations the First Island Chain runs down the northern part of Indonesia and on to Singapore, and thus includes all of the area enclosed by China’s infamous ‘Nine Dash Line’, which has been used to define and justify its extended claims on the territorial waters of Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia.

Land based anti-ship missiles on the mainland already cover an area far beyond the First Island Chain, and almost as far as the Second Island Chain. But missile systems have also already been deployed on some of the man-made (or artificially expanded) islands and reefs in the South China Sea – most notably on Woody Island, the largest of the Paracel islands – further extending their reach. The deployment of 124 mile (200 kilometre) range HQ-9 surface-to-air missiles (a derivative of the Russian S-300 system) to islands and reefs where there are already Chinese military bases and airfields would provide Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) coverage over large areas within the Nine Dash Line, while fighters or a longer range SAM system, like the Russian S-400 – designed to engage targets out to 250 miles (400 km) using 40N6 missiles – could create overlapping MEZs covering the entire area.

By extending the deployment of surface-to-surface weapons to the Fiery Cross, Subi, and Mischief Reefs virtually the whole area within the ‘Nine Dash Line’ would lie within the range of the 250 mile (400km) range YJ-62 ASCM (anti-ship cruise missile), while the 950 mile (1,550km) range DF-21 MRBM would be able to threaten Malaysia, Singapore, and most of Indonesia.

The 1,367 mile (2,200km) CJ-10 LACM would extend the area at risk to Jakarta and Palau. Even without these weapons, the DF-26B intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), can hit targets out to distances of between 1,864 miles and 3,417 miles – placing Guam and even New Delhi at risk.

Ending US dominance

Developed to counter US and allied multi-domain power projection platforms like carrier strike groups and long-range bombers, China’s A2/AD capabilities aim to remove the advantage of uncontested air (and maritime) dominance that the US has enjoyed in recent campaigns, and to erode the freedom of action that such dominance has afforded. Put simply, the aim is to be able to impose cost on enemy forces operating within the area covered by an A2/AD ‘umbrella’, and to make the preferred US model of expeditionary warfare increasingly difficult, putting at risk the safe bases and sanctuaries upon which the previous approach depended.

China relies on fighter aircraft and an intricate network of air and missile defence platforms for area denial, and has made real efforts to improve its air defence capabilities, deploying Shaanxi Y-8J, KJ-200H, KJ-500 and KJ-2000 airborne early warning aircraft, and Y-8CB, Y-8DZ, Y-8JB, Y-8JZ and Y-9DZ electronic intelligence platforms, Y-8G and Y-9G jammers and the Y-8T Airborne Command Post, as well as a variety of tankers. Its fighter force now includes the notionally ‘fifth generation’ Chengdu J-20, while the J-35 (broadly equivalent to the F-35) is under development. Other PLA Air Force fighters will soon deploy the new PL-20 and PL-21 very long range air-to-air missiles – intended to take down high-value assets such as airborne early warning and tanker aircraft. These weapons would further enhance area denial capabilities by forcing US force-multipliers like tankers and EW aircraft to operate further back, or risk being shot down. The effect is to turn a benign environment into a more contested one, and to force the US and its allies to return to having to face the real prospect of suffering losses in a peer-level conflict.

Playing Catch-up

Surprisingly, the US seems to have failed to do anything much to try to prevent the deployment of China’s A2/AD systems while they were being developed and initially deployed, or even to develop effective counters. Perhaps this was because it was felt that there was nothing that could be done – or perhaps because the US failed to fully comprehend early enough what was happening.

China advanced its A2/AD strategy while the US was fighting successful campaigns in the Balkans and the Middle East. These resulted in a degree of US complacency, and senior US politicians, officials and military commanders found it hard to conceive of another nation challenging US military power. Later, the Pentagon became distracted while fighting less successful counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan.

And while the US has had to project power across the globe, Beijing has been laser-focused on regional hegemony and on Taiwan, and has bolstered its A2/AD capabilities in an effort to place US forces at risk over more and more of the region.

It has to be acknowledged that while A2/AD capabilities may give an opponent the ability to threaten or even shape a space, they do not allow that enemy to wholly control that space, and they may be insufficient to prevent or limit tactical and strategic offensive operations within it.

The use of Low Observable aircraft, well supported by SEAD and electronic attack may not be sufficient to allow the degree of air dominance that US pilots have been used to, and may not allow them to be able to operate entirely unmolested. But it may well be enough to allow some elements of US air power to operate without suffering prohibitive losses, and for those elements to achieve their operational goals – especially if they are able to use very long range stand off weapons to stand well back from their targets.

But A2/AD does more than merely creating a contested space out of one that may previously have been uncontested or benign. Although tactical aircraft might be able to operate within China’s A2/AD ‘bubble’ without suffering an unsustainable loss rate, they might not be able to penetrate it far enough to be useful. Given that not all targets will be conveniently located close to the enemy coast (and in China they may be a long way inland), US aircraft may have to get close to the coast before launching their stand-off weapons. This will entail launching from bases or aircraft carriers that are well within the range of enemy missiles, or making a final refuelling from a tanker within about 500 miles (800km) of the missile launch box. This may make the mission effectively unflyable.

This is because larger and more vulnerable enablers and support aircraft, including airborne early warning and control (AEW&CS) platforms, EW aircraft, and most crucially of all, air-to-air refuelling tankers, may not be able to operate so far forward, and could be pushed so far back that they are unable to support the fighters and attack aircraft.

In one US large scale wargame, US combat air platforms achieved their initial goals, only to find that all of their tankers had been shot down as they returned for post strike refuelling, and therefore ran out of fuel before they could return to base!

There has been some pushback even against using the term ‘A2/AD’ on the basis that it creates a disproportionate impression of vulnerability and thereby gives too much credit to potential adversaries.

Less Effective

Certainly operational experience in Syria and the Ukraine has indicated that the effectiveness of even the latest double-digit surface-to-air missile systems is lower than was once supposed. Logically it would follow that SAMs create smaller and less effective A2/AD bubbles than has sometimes been assumed. Whether or not this is the case, the use of LO technology on aircraft and air-launched platforms makes US air power hard to stop!

Nor can China rely on its ballistic missiles to knock out US air power on the ground. In 2013, the United States deployed a Lockheed Martin Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) battery to Guam to protect the base against ballistic missile and other threats, while Raytheon Patriot/PAC-3 batteries were deployed to protect its military bases on Okinawa. These land based missile defence systems are augmented by some 17 Aegis BMD-capable vessels deployed in the Pacific.

As well as protecting these main bases, the US is adopting an agile employment doctrine that will see US forces deploying to remote airfields across the Pacific region rather than to main operating bases. These airfields will have their runways lengthened where necessary, and will be provisioned with pre-positioned spares, repair equipment and fuel. More capable command-and-control systems will be fielded to co-ordinate the operations of more widely dispersed forces. This promises to complicate Chinese targeting, and to reduce the risk of losing assets in a pre-emptive strike.

While China’s A2/AD capabilities may have no more effect on US air power operations than imposing a higher attrition rate, they may be more effective in the maritime domain.

Surface vessels represent big and vulnerable targets, whose loss would be harder to stomach than the loss of a fast jet or two. Moreover, considering the limited combat radius of carrier-borne aircraft without large-scale support from aerial refuelling tankers, the ability to keep an American carrier battle group at arm’s length may be all that China’s A2/AD capability needs to achieve if it is to ‘dissuade, deter, or, if required, defeat third-party intervention against a large-scale, theatre-wide campaign” mounted by China’s People’s Liberation Army.’ Such as might be required in a Chinese invasion of Taiwan!

Flashpoint Taiwan

China’s growing military confidence has been reflected in an increasingly belligerent approach to its regional neighbours, and many believe that Taiwan is rapidly becoming the world’s most dangerous flashpoint. The head of US Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Phil Davidson, warned the US Senate that China could try to annex Taiwan “in this decade, in fact within the next six years.” LtGen. S. Clinton Hinote, US Air Force deputy chief of staff for strategy, integration and requirements has pointed out that: “Three of China’s standing war plans are built around a Taiwan scenario. They’re planning for this. Taiwan is what they think about all the time.”

China’s A2/AD capabilities will complicate any US response to such an operation, and may even prevent the US from intervening at all. While US Air Power might be able to operate in the face of China’s A2/AD, there are real concerns that in a modern multi-domain conflict in the Pacific, America could struggle to stop Chinese forces from invading Taiwan.

Bonnie Glaser, director of the China power project at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSII) in Washington, revealed that in: “Every simulation that has been conducted looking at the threat from China by 2030, and there have been various ones carried out, for example in the event of China invading Taiwan, have all ended up with the defeat of the US.”

LtGen. S. Clinton Hinote says that: “The trend in our war games was not just that we were losing, but we were losing faster.” Hinote concluded that: “If the US military doesn’t change course we’re going to lose fast. In that case, an American president would likely be presented with almost a fait accompli.”

On the other hand, more and more effective countermeasures may become available to protect warships and air bases against long range cruise missiles and ballistic missiles, and perhaps even to protect vulnerable US tankers and other enablers.

But that may not be the point, since some have suggested that China’s A2/AD strategy may be a political rather than a military tool. The suggestion is that the strategy is intended to shape the peacetime environment in order to allow China to advance its strategic interests without recourse to military power, and not as an aid to actual war-fighting. The strategy has already disrupted freedom of navigation for US Navy and allied forces operating in the disputed and increasingly tense waters of the South China Sea, and may already have introduced doubt among the USA’s Pacific allies regarding the ability of US Pacific Command (USPACOM) to respond to Chinese pressure.

by Jon Lake