Published in the November/December 2020 Issue – Unmanned systems manufacturers are finding a responsive market for their products among navies in the Indo-Pacific region.

The expanding use of unmanned systems by naval forces in the Asia-Pacific region is gathering pace. The ability of unmanned air (UAS), surface (USVs) and underwater (UUVs) or remotely operated or autonomous underwater vehicles (ROVs and AUVs) to provide a range of capabilities is being realised.

Some countries are investing heavily in unmanned platforms as a way of plugging a gap in Intelligence, Reconnaissance and Surveillance (ISR) or taking the man out of the minefield in mine countermeasure (MCM) operations. Meanwhile others require unmanned systems to provide coverage over large expanses of maritime territory as a cheaper alternative to expensive manned assets.

The capability of the systems being acquired depends largely on available budgets. At one end of the scale Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam have ordered the ScanEagle UAS from Boeing Insitu via a US Foreign Military Sale (FMS) request. Indonesia and the Philippines will get eight each, Malaysia 12, Vietnam six. It is unclear whether deliveries have been completed as Boeing and the US Navy refused to comment.

ScanEagle is a small fixed-wing UAS designed for long endurance naval ISR operations with an assorted array of sensors and uses a catapult for launch and a pole for recovery. It has been in-service for some time with various militaries including the US Navy and is cheap, proven and a reliable option for smaller countries on limited budgets.

The Philippines Air Force is also acquiring nine Hermes 900 Medium Altitude Long Endurance (MALE) UAS and three Hermes 450 tactical UAS from Israeli company IAI along with Skylark UAVs from Israel’s Elbit Systems. This will provide a much-needed boost in maritime ISR for the government in Manila.

Malaysia is also pushing ahead with plans to enhance its maritime security capabilities releasing a tender that includes three medium-altitude long endurance (MALE) UAS as well as long-endurance unmanned aerial systems. This is part of Kuala Lumpur’s 12th Malaysian Plan that sets out procurement for 2021-25.

Another popular UAS with a wealth of naval experience is the S-100 Camcopter rotary UAS from Schiebel. The company signed a contract with the Royal Thai Navy (RTN) in November 2019 and stated that the S-100 would be deployed in Thailand and on RTN frigates “to deliver land and sea based ISR operations. This is the first time the RTN will be using Vertical Take Off and Landing (VTOL) UAS for maritime operations.”

Australia has requirements for naval UAS under SEA 129 Phase 5 Tactical UAS programme and both Schiebel and Insitu are involved in the trials phase providing the S-100 and ScanEagle respectively. The RAN has already acquired both platforms under the Navy Minor Project 1942 for its 822X Squadron that tests UAS. So far the squadron has completed trials from MV Sycamore the Anzac-class frigate HMAS Ballarat.

SEA 129 Phase 5 will provide the UAS solution for the RAN’s new Arafura-class Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs) and ANZAC-class frigates. In August invitations to respond to the programme were announced. The RAN plans to introduce the systems through a series of block acquisitions to allow for future updates and technological innovations to be included. This initial invitation is for UAS for the initial block of capability from 2024-2028 and will be used to prove the system operationally and its further development. The Commonwealth will then down select the finalists that will then participate in a Request for Tender (RFT).

The second block that will follow from 2029-2033 will installed on the new Hunter-class frigates while a third block from 2034-2038 will include a technology refresh and adaptations to meet changes in operational requirements.

Australia is one of the countries in the region that is making a large investment in unmanned systems. As a large country with a considerable exclusive economic zone and wider regional interests, the use of unmanned systems to expand ISR and its maritime security presence is a cost-effective way of generating capacity.

Unmanned mine hunting

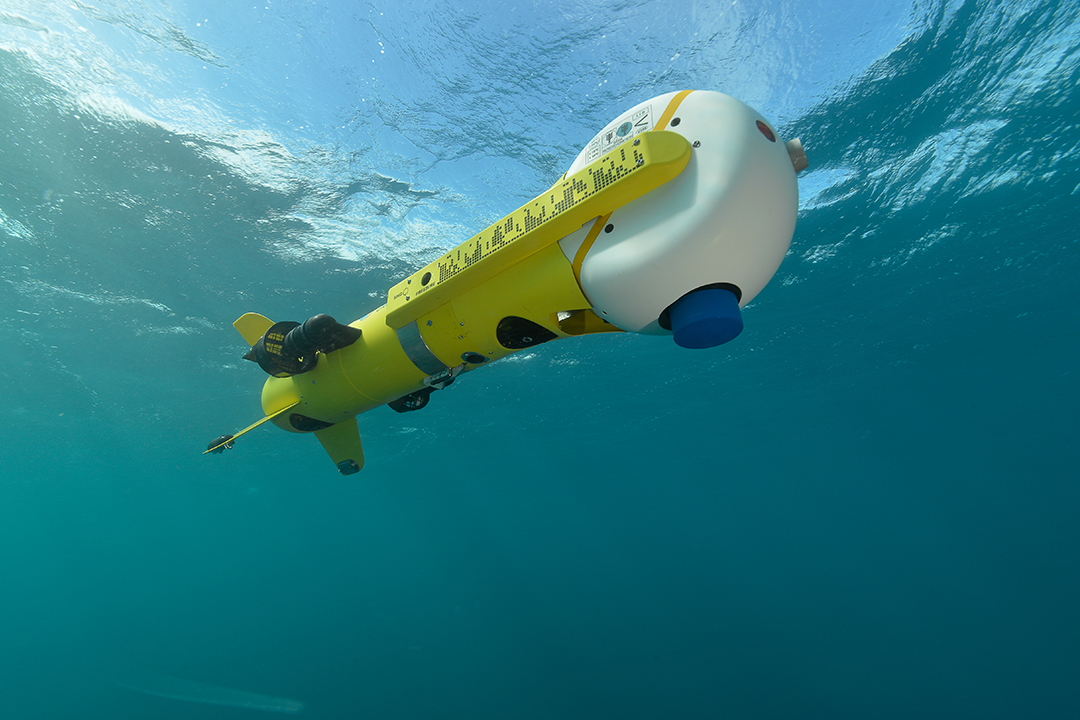

This is of particular importance when it comes to Mine Counter Measure (MCM) operations where Australia is running three separate programmes. The first is SEA 1778 Phase 1 which aims to introduce a deployable MCM capability that can be taken on the RAN’s amphibious ships on operations. General Dynamic Maritime Systems has been contracted to provide four Bluefin-9 and three Bluefin-12 AUVs for mine detection. These will operate alongside five 35ft (10.6m) USVs from Steber International. General Dynamics did not respond to requests for an update on its work but an initial operating capability (IOC) is expected in 2020 following the successful testing of systems by the Australian Mine Warfare Team 16 (AMWT-16) in February 2020.

Meanwhile Project SEA 1905 will introduce a range of unmanned systems – known as toolboxes – that will replace the RAN’s Huon-class coastal minehunter (MHC) ships. These will be deployed from the new Arafura-class OPVs and two new MHCs based on the OPV design as an organic capability, but a lot will depend on how SEA 1778 develops. Gate One approval is expected in 2020. To further investigate USV capability, Australia’s DST has provided funding of $4 million (AUS$5.5 million) to Ocius Technology to build and test its Bluebottle USV as a gateway platform to communicate with underwater assets such as AUVs.

Robert Dane, CEO of Ocius Technology, told AMR: “We’re building five ‘next-gen’ Bluebottles to deploy out of Darwin in 2021 – to demo an intelligent networked ‘squad’ doing three different roles in three different Areas of Operation.” Those three areas of operation are classified but Dane said the applications will be for “guarding an asset such as a port and oil rig; patrolling the EEZ; and anti-submarine warfare.”

The third project is SEA 1770 to acquire a Rapid Environmental Assessment (REA) capability. Hydroid’s Remus 100 AUV has been acquired for the Maritime Geospatial Warfare units that operate within four Deployable Geospatial Survey Teams with the RAN’s Hydrographic, Meteorological and Oceanic Group. Tom Reynolds, senior director, Business Development, Huntington Ingalls Industries, Technical Solutions – which owns Hydroid – told AMR that while individual customers could not be named, Remus has been sold to 24 navies “including five navies in the Asia-Pacific region.”

Meanwhile the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is expected to receive the Northrop Grumman M-4C Triton UAS under Project AIR 7000 Phase 1B. The company initiated the construction of the first platform on 28 October. Australia has ordered three with up to six planned. The company is also providing four of its RQ-4 Block 30 Global Hawk high-altitude long endurance (HALE) UAS to South Korea under a $657 million FMS contract with the US signed in 2014. The first two were delivered at the end of 2019 and April 2020 with the remainder due by the end of the year.

Northrop Grumman believes that the first export of its MQ-8C Fire Scout will be to Japan. Japan is developing plans for unmanned naval systems procurement and is completing tests with the MQ-9B SeaGuardian. A spokesperson from General Atomics (GA-ASI), which manufactures the MQ-9B, told AMR that a series of validation flights for the Japan Coast Guard with SeaGuardian started on 15 October. The flights will “validate the wide-area maritime surveillance capabilities of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) for carrying out JCG’s missions, from search and rescue to maritime law enforcement.” He added: “These flights follow successful MQ-9 maritime patrol demonstrations in the Korea Strait in 2018 and the Aegean Sea in 2019. The current flight series features the MQ-9B SeaGuardian, capable of all-weather operations in civil national and international airspace.”

Elsewhere the GA-ASI spokesperson said that RPAS from GA-ASI “is being considered under the FMS route between the Indian and US governments”. India is looking for about 10-12 systems and the SeaGuardian is under consideration. However, despite approval from the US Government for an export in 2017 a sale has not been concluded as India has ambitions to develop its own UAS, although it has struggled to bring new platforms to production. A new 440lb (200kg) rotary UAV (RUAV) from Hindustan Aeronautics (HAL) that was unveiled in 2019 is expected to begin testing in 2021. India wants 10 UAS to be deployed from its warships. Meanwhile IAI signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with HAL in early 2020 to develop UAS such as the Heron and Searcher.

In the underwater domain India released Requests for Information (RFIs) in 2018 for a High Endurance Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (HEAUV) and a new USV, although beyond this it is unclear if any programmes have been initiated.

ECA Group has delivered its Mine Identification and Neutralisation Systems worldwide including to Singapore. K-ster has been tested with the Venus 16 USVs that have been delivered by ST Electronics to prove a new MCM system. Singapore already has the Protector USVs from Rafael for base protection, but these will be used for coastal defence. Meanwhile the Republic of Singapore Navy has also embarked on its own unmanned systems development with a new MCM USV that employs a towed synthetic aperture sonar (T-SAS) from Thales.

China also has plans to speed up the development of its maritime unmanned systems. Although there is little public information about its projects, a new VTOL UAS mock-up (similar to the Fire Scout) has been seen on the deck of the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s (PLAN) Type 075 Landing Helicopter Dock. The WZ-9 Soaring Dragon HALE and BZK-005 MALE UASs have also been seen near airbases over the past five years. The SD-40 Sea Cavalry has flown from a Type 052C destroyer and China has already developed the CH-family of UAS and exported them. Meanwhile it is reported in Chinese media that there are plans for an extra-large UUVs (XLUUV) in the future to counter US prototype developments.

The unmanned revolution in Indo-Pacific navies will progress at different speeds depending on the resources available but it is clear that all countries will be acquiring these capabilities for the future. Whether in-country development, the purchase of expensive or cheap systems, the growth of unmanned systems in all domains will escalate.

by Tim Fish