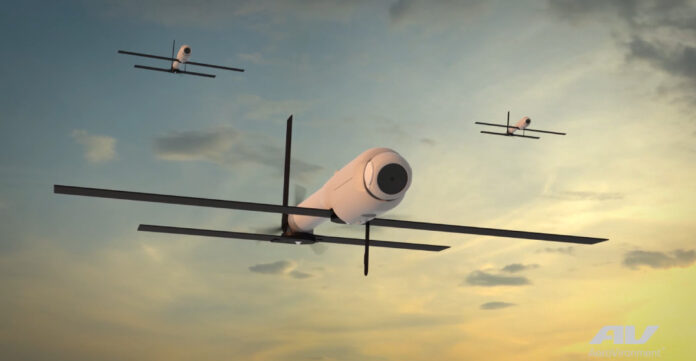

Loitering munitions have already proved their effectiveness in conflict and their development in terms of range and deployment methods continues to be explored.

Loitering munitions are becoming the new ‘must-have’ weapon in military inventories. The successful use of these weapons in recent conflicts from the Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan in September-November 2020, to the Yemen proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran and the start of the Russo-Ukraine War in February 2022, has spurred procurement efforts.

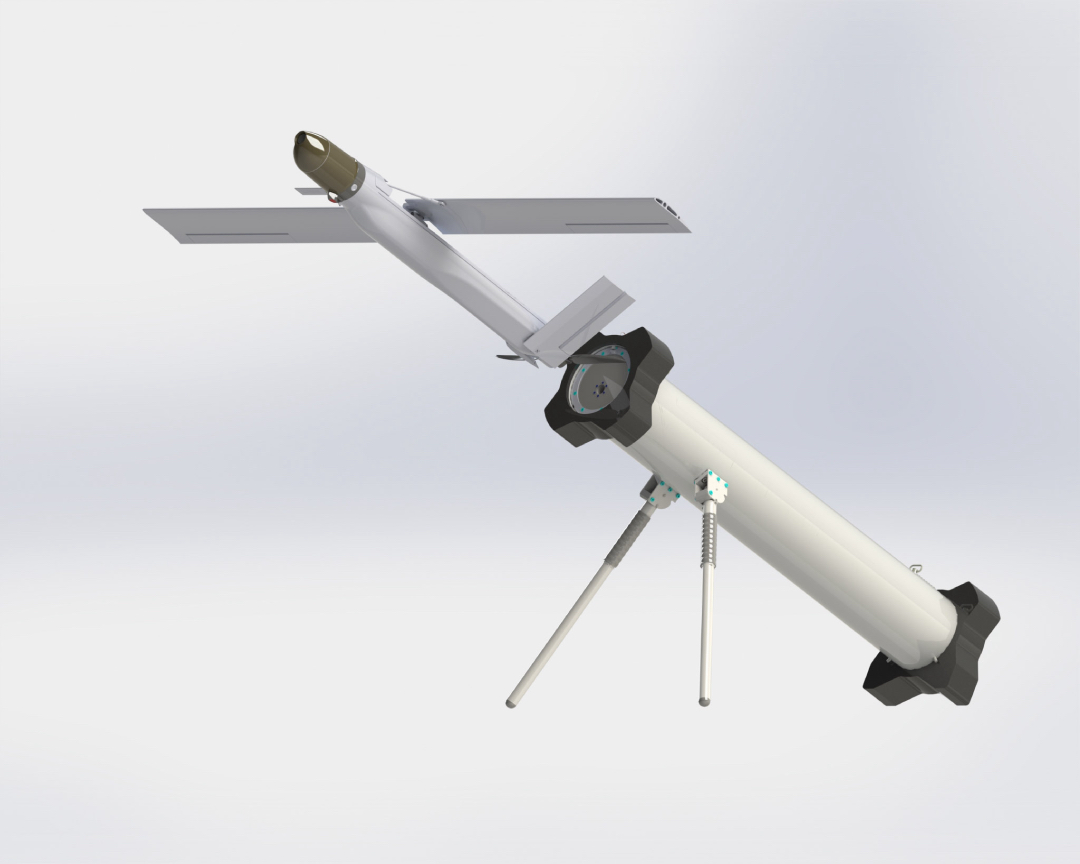

The capabilities that loitering munitions offer sits somewhere between an Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) and a missile. The ability to ‘loiter’ in a designated area for hours and search for targets means these munitions behave in a fashion similar to UAS running on a fuel-powered propulsion system and employing different wing-shape designs for mobility in the air. However, like missiles, loitering munitions are often launched from canisters and are expendable, fitted with a seeker and warhead to destroy the targets required.

AeroVironment, an UAS company that manufactures the Switchblade loitering munition, offered this description: “A loitering missile, sometimes called a ‘kamikaze drone’, is a category of small unmanned aerial systems equipped with a munition that can loiter, or wait passively in the air, and attack once a target is identified,” a spokesperson told Asian Military Review.

Loitering munitions offer a ranged precision strike capability that sits between that offered by artillery guns and missiles. They have the range to strike beyond the reach of artillery shells, but are not fast or lethal enough to engage targets that missiles can hit at much longer ranges. However, they are much cheaper to produce than missiles, can operate in swarms and are small and light enough to offer an organic strike capability to smaller units operating in a dispersed way to avoid detection.

The AeroVironment spokesperson said that the great advantage of loitering munitions versus traditional artillery is their “ability to reach greater range, maintaining a safer stand-off for forces. In addition, their small size and low acoustic, visual and thermal signature make them difficult to detect, recognise or track, even at close range.”

These attributes mean that loitering munitions occupy an important place in a military arsenal but it is unlikely they will change the face or warfare to any considerable degree. Loitering munitions were important but not decisive in Nagorno-Karabakh and Yemen and alone they will not beat Russia’s invading army in Ukraine.

Speaking to AMR, Doug Barrie, the senior fellow for military aerospace at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) defence think tank, said: “Loitering munitions have a real place in the inventory and they are not going to disappear, but on their own are they a war-winning technology – no.”

AeroVironment’s Switchblade Tactical UAS gained notoriety after the US announced in May that it was exporting 700 munitions to Ukraine as part of an additional $150 million towards its $4.5 billion security assistance package. The Switchblade 300 has a 5.3 nautical mile (10 kilometre) range and endurance of about 15 minutes. Weighing just 5.5 pounds (2.5 kilogrammes) it is tube-launched, can be carried and operated by a single soldier who can finds targets using on board electro-optical cameras and an Infra-Red (IR) camera. The larger Switchblade 600 has an anti-armour capability and has an endurance of an hour.

The company did not comment on specific in-theatre use but the spokesperson said that both variants of Switchblade are “uniquely suited for this type of conflict in Ukraine” adding that both are man-portable and can be operated at the unit level.

Ghost Hunting

The Phoenix Ghost built by Aevex Aerospace is another loitering munition that is being sent by the US to Ukraine. Until it was announced in April by the Biden administration, there was little know about it. There is little information about it in the public domain beyond a general description that it is a small munition with a similar capability to Switchblade and has been developed by the US Air Force specifically for operations in Ukraine.

The development of more advanced technologies in sensors, communications and networking, autonomy and targeting mean that these latest loitering munitions are different from early versions of the weapon. Loitering munitions were first developed after the Vietnam War, inspired by “Wild Weasel” McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom and Republic F-105 Thunderchief flights against Surface-to-Air (SAM missile sites. They made their first appearance in the 1980s as a tool for the Suppression of Enemy Air Defences (SEAD).

The SEAD role is usually undertaken by an electronic warfare-capable aircraft like the Boeing EA-18G Growler, which can detect enemy air defence radar and launch an anti-radiation munition against them. This allows the entry of strike aircraft to hit other targets. However, countries that could not afford these expensive aircraft could instead use loitering munitions for SEAD. They were pre-programmed and launched in advance of an air strike equipped with a radio frequency (RF) seeker that can detect air defence radar and automatically engage them.

However, as new technologies have come on stream it has enabled loitering munitions to undertake different roles. Using EO/IR sensors and communications networks allows a human-in-the-loop to view targets using a live video downlink and direct the munition to attack. Unlike the SEAD variants, where the RF seeker will only locate military signals, when using EO/IR systems for targeting the operator confirmation of target sets is necessary to avoid mistakenly destroying civilian vehicles or buildings through a greater level of precision by providing eyes on target.

“As we are witnessing in Ukraine, conflicts of today, and into the near future, are going to be heavily unmanned,” the AeroVironment spokesperson said. “The sophistication of these smaller assets requires the most advanced technology in terms of processors, cameras, and other sensors for example – involving multiple fields of science.”

The impact of digital technology means that more processing power can be packed into an increasingly small space combined and with the low cost of sensors. This means loitering munitions can offer greater utility than previously possible. This ability to conduct precision strike on a wide variety of targets including personnel, armour, structures as well as SEAD at range in a cost-effective manner make loitering munitions a very valuable asset – but they are not a silver bullet.

“What you don’t want to do is pack these things full of expensive technology because they are not coming back,” Barrie said, so capabilities of loitering munitions will be limited by the need to keep costs down. If costs increase too much then it will be more effective to employ a precision-guided missile that is faster, has longer range, carries a larger warhead that can destroy more targets. Missiles are more capable against air defence systems offering a higher guarantee of success securing a kill. If a loitering munition fails to destroy a target, it not only alerts the enemy to the presence of forces nearby within the range of the munition, but they’ll move and then target the launcher. There is a balance to achieve between the level of capability for these weapons and specific target sets to engage with them and cost.

There are further limitations, Barrie added, because any system that is “dependent or partially dependent on data link technology with a human in- or on-the-loop, becomes more difficult in an environment where the electro-magnetic spectrum is heavily contested with jamming and spoofing.” In addition, because loitering munitions are relatively slow moving, when they are used to engage a moving target (unless the weapon is close to the target) it will potentially have moved by the time munition arrives – so it needs to be deployed and loitering in the right area to engage as soon as the target is found.

Asymmetric Advantage

The extent that loitering munitions will be useful in battle depends on the warfare environment. Recent conflicts have seen rival forces engaging in operations against each other with little in the way of effective or persistent air defence. If they are employed in a counter-insurgency campaign where an enemy has limited air defence and ISR assets then loitering munitions can give forces using them the upper hand.

“The use of loitering munition technology by Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, with a combination of UAS – both armed and for intelligence gathering – alongside loitering munitions was shown to be effective against weak or poor air defences,” Barrie said. Azerbaijan used Israeli loitering munitions including the IAI Harop and Elbit SkyStriker to engage Armenian armoured vehicles including the Uralvagonzavod T-72 tank and MZiK S-300 air defence system.

In the Libyan civil war it was reported that Polish-built Warmate loitering munition from WB Group have been used. In Yemen, the Houthi rebel group Ansar Allah has deployed the Iranian HESA Qasef1 and their own Samad-2 and -3, although these are more like UAS with a warhead attached. These weapons proved their usefulness in such environments.

“On the other hand, if you are facing a peer rival with similar equipment, reasonable air defences, ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) assets and a combat air capability, then vehicle launch systems will be a priority target in the first few days of the conflict,” Barrie said.

According to a June 2022 CNA report entitled Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy in Russia, Rostec announced that the KUB and Lancet loitering munitions, both built by Kalashnikov, had been used by Russia in Ukraine to strike ground targets. But it stated that there was little evidence of either being successful and said that earlier in the war “several KUBs were either downed by the Ukrainian military or crashed in civilian neighbourhoods without detonating, suggesting either a successful Ukrainian countermeasure or an internal malfunction.”

Although loitering munitions offer a stand-off strike capability, the larger ones still only have a range of up to 27-54nm (50-100km) and therefore the launchers will be vulnerable to long-range missiles or air attack. Furthermore, once in the air – although they are small and hard to detect – loitering munitions are slow moving and this makes them vulnerable to anti-air defence systems. It means that units operating loitering munitions will have to be well hidden and mobile, with the weapons best used in an unpredictable fashion to make best use of their attributes.

“There is a utility for loitering munitions in Special Forces-type operations at the smaller end of the scale where they can be carried in a bergen, [giving them] an ability not just to look over the next hill or street, but when a target is found, to actually engage it,” Barrie said. “It can give smaller units organic firepower and the ability to attack at range and with precision whereas previously other platforms – fixed-wing, rotary, artillery – would have to be called in to conduct a strike.”

In Syria, it was reported that Russian special forces were using the Lancet-1 and -3 loitering munitions from Zala Aero Group.

Urgent Operational Need

The US Army has been buying Switchblade 600 and 300 systems under successive contracts with AeroVironment. One contract in April 2020 was worth $76 million and another in April 2021 worth $45 million, acquired under an Urgent Operational Need Statement. The Army is also buying the Altius-600 loitering munition under its Air Launched Effects (ALE) programme. ALE is designed to test swarming tactics, which will be the next significant development for loitering munitions as a way of overwhelming air defences, providing decoys and striking lots of targets.

“If there is a surface-to-air missile battery in the area you could use a swarm of loitering munitions with a mix of decoys and actual loitering munitions that look the same,” Barrie explained, “This makes targeting much harder if there are 10 or so flying about in a coordinated attack and it is not possible to find the two that have warheads. It poses an inventory cost on the defender, which has to use its own munitions to eliminate all the loitering munitions or risk being destroyed.”

The question of the inventory cost for defenders comes down to the weapons that air defence systems will need to effectively counter loitering munitions in a cost-effective manner. If launcher platforms cannot be destroyed on the ground and swarms of loitering munitions are already airborne then point defence options will be needed. These are likely to be similar to the range of counter-UAS systems in use that include mix of electronic warfare (EW), rapid firing gun systems and high-power directed energy/laser weapons. These can rapidly destroy numerous targets at low cost.

Future developments of loitering munitions will include their use fired from unmanned adjunct or ‘loyal wingman’ aircraft. This will mitigate against the limited range and slow movement of loitering munitions by using a fast air platform to deliver it to the area of operations at the right time. It means that the loitering munition will operate in a similar fashion to missiles but with a loitering capability so it can engage an emitting target that has stopped emitting or use its sensors and precision to pinpoint a target.

“There’s going to be a fair amount of experimentation on this as armed forces try to figure out how best to employ loitering munitions in different ways to maximise their capabilities, or use them in a mix of effectors,” Barrie said.

As the proliferation and subsequent use of loitering munitions increases in the future, there will be more incidents when the weapons will be launched and are unable to find targets. As these weapons are not recoverable, more ways must be found to ensure that when they run out of fuel, they can find adequate space in or near the area of operations with few or no civilians to safely self-destruct without remaining a threat to the local population.

Autonomous targeting is also an issue for loitering munitions that raises a whole host of ethical and legal issues relating to international humanitarian law in armed conflict that have not been fully explored. But loitering munitions are here to stay and offer a valuable cost-effective stand-off strike capability that fits neatly above that offered by artillery systems and below that of missiles.

But these are still early days of their use. Loitering munitions have limitations and although development is continuing rival forces will acknowledge the early successes of these weapons in recent conflicts and start to employ more effective countermeasures. The ways in which loitering munitions are used operationally and the extent to which countermeasures can defeat them will dictate the level of their future utility on the battlefield.

by Tim Fish