While Japan has long been involved in the electronic warfare domain, the country’s navy needs to enhance its strategic EW capabilities.

Japan is an Electronic Warfare (EW) veteran. In an incident now worthy of the EW Hall of Fame, 116 years ago, the crew of a Royal Navy ‘Eclipse’ class protected cruiser stationed in the Suez Canal found that they could intercept Russian Navy High Frequency (three megahertz/MHz to 30MHz) radio communications. The Communications Intelligence (COMINT) gathered by the crew of HMS Diana on 28 January 1904 warned that the fleet of Tsar Nicholas II, who would be the last Emperor of Russia, was mobilising and heading into the Pacific. The intelligence was duly passed to the UK’s ally Japan, with the Imperial Japanese Navy performing a surprise attack on the Imperial Russian Navy stationed at Port Arthur, which today resides on the coast of Liaoning province in the northeast of the People’s Republic of China. The Russo-Japanese War was now underway.

COMINT collection would be performed by Japan during the conflict, with Russian communications intercepted and their codes broken. Over a century later, Japan continues to be heavily involved in the collection of Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) with the country’s JMSDF (Japan Maritime Self-Defence Force), like the country’s other armed services, reliant on this intelligence. SIGINT refers to the communications intelligence, and electronic intelligence, the latter of which mainly pertains to radar transmissions, collecting by SIGINT practitioners.

Threats

The JMSDF has much to worry about. Its maritime neighbourhood includes the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) of the People’s Republic of China to the southwest, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s Korean People’s Navy (KPN) to the west and the Russian Navy’s Pacific Fleet headquartered in Vladivostok to the northeast. Japan’s close relationship with the United States, and its strategic rivalry with the first two nations makes the Sea of Japan, the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea all areas of interest, and of potential tension, for the JMSDF. Professor Richard Tanter, a senior research associate at the Nautilus Institute, a think tank based in Berkeley, California and co-author with Professor Desmond Ball of The Tools of Owatatsumi, a seminal discussion of Japan’s SIGINT gathering apparatus, told AMR that over “the past three decades Russia concerns have been surpassed by perceived North Korean and (on a much larger scale) China threats, (particularly) China’s expanded regional pattern of intrusion into Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and defence-sensitive locations.” Moreover, the Japanese government is wedded to a doctrinal requirement for the JMSDF to protect sea lines of communications up to 540 nautical miles/nm (1000 kilometres/km) from the country.

Little surprise then that the EW capabilities of the JMSDF and Japan’s armed services writ large have evolved to address these potential threats, and also disputes with the Republic of Korea (ROK) over the jointly claimed Dokdo/Takeshima Islands in the southern Sea of Japan and with Taiwan over the sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands northeast of the island. Prof Tanter argues that “it isn’t really possible to describe the Republic of Korea as an ally of Japan, much to the despair of US alliance planners.” Consequently “precise levels and areas of Japan-ROK intelligence sharing have been difficult to track, other than through the public vicissitudes of the Japan-ROK GSOMIA (General Security of Military Information Agreement).” The GSOMIA as an intelligence sharing pact between Japan and the ROK which also involves the US, intended to enhance intelligence sharing vis-a-vis the DPRK. The pact has come under marked strain in recent years against a backdrop of tensions between Japan and the Republic of Korea regarding the former’s colonial rule of the Korean peninsula between 1910 and 1945, and Japan’s conduct there during the Second World War.

The JMSDF’s SIGINT posture rests on the collection of COMINT and ELINT by ground installations, warships and aircraft. The principle clearing house for all SIGINT received by the JMSDF is the Ocean Surveillance Information System (OSIS) based at the navy’s fleet headquarters in Yokosuka, on the southern coast of Honshu island.

Shore Stations

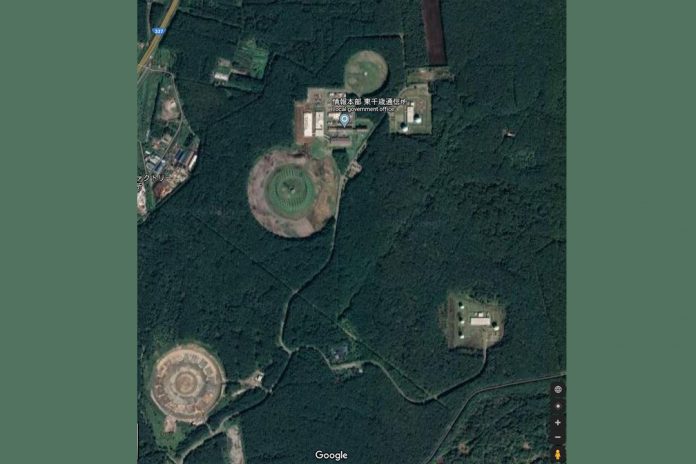

The Japanese government maintains several ground stations operated by the JMSDF tasked with collecting SIGINT including HF traffic from shipping with a high emphasis placed on the location of these signals as a means of tracking vessels of interest. Stations are located in Miho on the west coast of Honshu Island, and at Chitose on the southern coast of Hokkaido Island. This latter station is primarily tasked with intercepting HF traffic from the Russian Far East, which almost certainly includes Pacific Fleet HF traffic. The SIGINT facility on the island of Kikai-Jima at the southern tip of the archipelago performs a similar role although it is likely to be largely concerned with collecting COMNIT from the PRC. Other COMINT collection facilities are based at Wakkanai, on the northern tip of Hokkaido which may be tasked with collecting COMINT from the DPRK and Russia, Nemuro in northeast of the island; Kobunto on the west coast of Honshu, also probably focused on the DPRK; Tachiari in the north of Kyushu, south of the ROK and at Ishigaki in the south of the Ryukyu archipelago west of Taiwan. Additional ground stations have been completed in the city of Miyakojima on Myako Island in Okinawa prefecture, Japan’s southernmost prefecture, and two additional stations on the island of Yonaguni one of Japan’s westernmost inhabited islands. A station has also been constructed on the island of Iwo Jima in the Bonin Island archipelago 540nm (1,000km) south of Tokyo. Prof Tanter says that the construction of these stations means that Japan now has a SIGINT gathering apparatus which covers the entirety of the country’s 110,199 square nautical mile (377,975 square kilometre) EEZ; the eighth largest in the world.

Vessels

Ships operated by the JMSDF thought to be used for SIGINT collection include the polar icebreaker Shirase which and three oceanographic research vessels, the Futami, Nichinan and Shonan, open sources state, may assist SIGINT gathering efforts. Nonetheless, some sources say that these vessels are primarily concerned with the collection of acoustic intelligence. Prof Tanter argues that as these vessels “are inadequate to extend their SIGINT role to match further seas ambitions” for Japan. Japan’s warships, particularly its large surface combatants are outfitted with Electronic Support Measures (ESMs) capable of gathering COMINT as well as ELINT. At best these will be capable of collecting such intelligence at the tactical and operational levels, in support of a task group. The problem for the JMSDF is that it lacks the capability to collect SIGINT at the strategic level. This could become an increasingly pressing priority in the Asia-Pacific as tensions with the DPRK and PRC show no immediate signs of lessening. It might become prudent for the JMSDF to invest in a strategic SIGINT gathering vessels, although there are no immediate signs that such an acquisition is in the offing.

Aircraft

Although the JMSDF lacks dedicated SIGINT collection vessels, this is not the case for aircraft. The fleet has four Lockheed Martin EP-3C SIGINT aircraft, closely based on the EP-3Es flown by the US Navy. It is possible that the division of labour sees the shore stations tasked with the strategic collection of ‘raw’ SIGINT data which is later analysed and shared with the JMSDF and Japan’s other armed services. Conversely the ships and aircraft may collect SIGINT which is used at the operational level directly by the JMSDF and by Japan’s air and ground self defence forces. For example, ELINT collected by the EP-3Cs concerning potentially hostile ground-based air surveillance or fire control/ground controlled interception radars would be of great interest to the air force alongside the navy. ELINT and COMINT gathered by JMSDF assets is believed to be analysed by the navy’s Electronic Intelligence Centre which will also receive and process ELINT delivered from Japan’s other defence and intelligence communities. Thoughts are now turning to the EP-3C’s replacement. Japan is currently flight-testing its new Kawasaki EC-2 ELINT platform which is expected to enter service with the JASDF over the coming year. This same platform could yet replace the JMSDF’s EP-3Cs.

this aircraft will be replaced in the future by a version of the EC-2 SIGINT aircraft equipping the JASDF.

International Cooperation

Beyond the capabilities discussed above, the JMSDF continues to maintain close links with the US Navy. This is highly apparent in the intelligence-sharing arena and is illustrated, Prof Tanter says, by the colocation of the US Navy Seventh Fleet and the JMSDF headquarters at Yokosuka naval base on the southern coast of Honshu. He continues that the US Navy and JMSDF collaborate in several initiatives: For example, the SIGINT obtained by the JMSDF platforms discussed above is fed into the force’s Ocean Surveillance System (OSIS) and some of this data is shared with the US Navy, Prof. Tanter continues. The OSIS also includes acoustic, ELINT and imagery intelligence drawn from JMSDF underwater acoustic sensors, coastal radar stations, maritime patrol aircraft, naval and coastguard vessels. Meanwhile the Japanese government’s Misawa satellite station in northeast Honshu acts as a ground station receiving raw ELINT from the US Navy’s Naval Ocean Surveillance System constellation of 18 Intruder satellites operational since 2001. It would be surprising if at least some of this ELINT was not shared with the US’ close ally and its host for the Misawa portion of the Intruder network.

Challenges

One of the major problems facing the JMSDF is that it is largely reliant on the JGSDF and JASDF for much of the relevant ELINT and COMINT it receives. The force will need to acquire new SIGINT aircraft, and will probably need a dedicated SIGINT vessel at some point in the near future if it is to develop an independent and capable strategic and operational SIGINT collection capability: “Apart from underwater surveillance, the JGSDF does most of the maritime surveillance,” notes Prof Tanter. With the EEZ fully covered with by SIGINT collection ground stations, Prof Tanter argues that investment is now needed into “surveillance ships and SIGINT satellites” alongside the extension of airborne SIGINT collection coverage into the South China Sea and the South Pacific: “The latter would depend in part on deeper interoperability and operational integration with partner countries” such as Australia and the US, Prof. Tanter continues. The JMSDF clearly needs to invest in its SIGINT collection, not only to aid the fleet, but also to feed into the wider Japanese intelligence apparatus.

On the one hand, investments to this end could herald billions of dollars of expenditure. Nonetheless, such capabilities in terms of ships, aircraft and the all-important ESMs that will equip them could easily be sourced domestically. It is noteworthy that the EC-2 is being built indigenously and, although specific details regarding its ESM are sparse, this will almost certainly be sourced domestically. Companies like Fujitsu and Mitsubishi Electric are acknowledged EW centres of excellence. While both have largely demurred from exports, as a result of Japan’s arms proliferation strictures, they are firmly established as domestic EW suppliers. The domestic approach allows Japan to remain independent in terms of reliance on electronic warfare equipment while exploiting the competencies in electronics and computing where the country has a justifiably enviable reputation.

That said, any global economic slowdown as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic could make its mark on the Japanese defence budget. In December 2019 Japanese defence expenditure increased for the eighth year running enjoying a 1.3 percent growth on the previous year to take defence spending to $48.6 billion until 2021. In total, the country’s defence budget has increased by 13 percent since 2012. A global recession could cause this trend to flatline or reduce in the coming years, particularly if Japan’s military and policy makers believe that the JMSDF’s SIGINT appetite can continue to be satisfied from existing capabilities owned by other services. It maybe 116 years since Japan helped raise the dawn of SIGINT, yet the Land of the Rising Sun will continue to face security challenges in the naval domain. The extent to which the JMSDF it can meet tomorrow’s security challenges will depend in part on Japan’s ability to procure today the SIGINT tools her navy will need.