The story of land-based medium- to long-range Surface-to-Air Missiles (SAM) in the Asia-Pacific is one of considerable contrasts. For example, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is fielding increasingly capable ground-based air defences with other regional powers left to play catch-up.

Alongside the PRC it is arguably only India that is close to developing a similarly-layered GBAD network. Other countries including Afghanistan, Australia, Brunei-Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka maintain Ground-Based Air Defence (GBAD) capabilities limited to man-portable and/or short-range SAM systems, as well as anti-aircraft artillery.

Among the long-range SAMs currently on the market, Russia’s Almaz-Antey S-400 Triumf is perhaps the most capable: with a range of up to 215 nautical miles/nm (400 kilometres/km) and the ability to engage ballistic missiles and aircraft with a low radar cross section. In 2015 both the PRC and India reached agreements with Moscow to acquire the S-400. The PRC became the first foreign customer for the system, as announced by Russian state arms export agency Rosoboronexport in April 2015. The $3-billion contract apparently includes four-to-six battalions, with deliveries to begin in 2017.

Valued at $4.5 billion, New Delhi’s S-400 deal was authorised by Indian lawmakers in December 2015, but as of January 2016 had apparently not been formalised. Prior to selecting the S-400, India had been linked with a deal for six Almaz-Antei S-300V SAM systems (see below) for Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD), but this order never materialised.

The closest Western-made counterpart to the S-400 is the Lockheed Martin MIM-104F Patriot Advanced Capability-3 (PAC-3). In the Asia-Pacific, the MIM-104F has been acquired by Japan, the Republic of Korea (RoK) and Taiwan. With an eye on BMD developments in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), in March 2015 the RoK signed a letter of agreement with the US government covering an undisclosed number of MIM-104F systems to be supplied via Foreign Military Sales (FMS) channels. The RoK’s Defence Acquisition Programme Administration, which oversees the country’s defence procurement, put a value of $1.1 billion on the deal, with deliveries of the MIM-104Fs due to commence in 2017 and conclude in 2019. In addition, $769.4 million will be spent on an upgrade for existing MIM-104C PAC-2 systems by Raytheon. The RoK and the US have also discussed a possible sale of the Lockheed Martin Terminal High Altitude Area Defence (THAAD) system, which provides defence against short- to medium-range ballistic missiles.

Yet to secure orders in the Asia-Pacific is the Arrow BMD system from Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI). However, the Arrow has been linked to a possible sale to Singapore and has also been studied by the RoK as an alternative to the THAAD. Furthermore, India has acquired two IAI Elta Systems EL/M-2080 Green Pine radars which usually accompany the Arrow SAM system, although these are apparently used with Russian-supplied SAM systems. Although unconfirmed by India, it is thought that these radars are either used to supply targeting information to the Indian Army and Indian Air Force’s (IAF) Almaz-Antey S-125 Neva/Pechora or mobile 9K37 Buk SAM systems, or for further development of indigenous BMD radar technology.

China

Until the arrival of the S-400 (see above), China’s GBAD network will be spearheaded by the Almaz-Antey S-300 family of SAM systems which has been acquired in successively more advanced versions. Eight battalions of the basic S-300PMU were delivered in the early 1990s which employed the 5V55U SAM which itself had a range in the order of 80.9nm (150km), followed by four battalions of improved S-300PMU-1 systems delivered between 1993 and 1997, and provided with 150 5V55R missiles. Compared to its predecessor, the 5V55R had a slightly reduced range of 48.5nm (90km) using terminal semi-active radar homing, in which the S-300PMU-1’s tracking and engagement radar provides target position updates to the missile by datalink for the full duration of the engagement, including the end game.

Beginning in 2003, China received another four battalions of S-300PMU-1 systems, now armed with the more capable 48N6 missile (150 examples acquired) which performed active radar homing in that the missile’s organic radar tracked its target. A typical S-300PMU-1 battery will include up to a maximum of eight transporter-erector-launchers, each with four 48N6 missiles ready to fire, with a battalion comprising six batteries, plus accompanying radar, command post and logistics provision. In 2008-2009 China took delivery of the definitive S-300PMU-2 Favorit system, under an $890-million deal that included eight battalions and 300 48N6E2 missiles, which have an enhanced range of 105.2nm (195km) compared to the 80.9nm range of the 48N6. An additional batch of 300 48N6E2 missiles has since been received. Reports indicate that an additional 15 batteries of an unidentified S-300 system were received in 2009 for deployment between Beijing and Shanghai. The PRC’s S-300PMU/PMU-1 is complemented by the indigenous China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC) HQ-9, which offers broadly similar capabilities. The HQ-9 reportedly entered production in 2005 and was confirmed as operational with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in October 2011. Older HQ-2B and HQ-2J systems, Chinese-made versions of the Soviet Almaz-Antey S-75 dating from the 1980s, remain in service for the defence of less critical areas of the country.

At the lower end of the range spectrum, the LY-60, a reverse-engineered version of the Italian-designed MBDA Aspide, is reportedly also in PLA use, under the local designation HQ-64. Controversy surrounds the status of the China Jianhnan Space Industry Company HQ-12. Some sources suggest around 60 examples of the truck-mounted HQ-12 are on inventory, while others indicate that any examples that were inducted were used for evaluation or demonstration purposes only. However, the assignment of an HQ- number around 2007 supports the idea that the system may have entered PLA service. Finally, the Shanghai Academy of Spaceflight Technology (SAST) HQ-16, the Chinese equivalent of the Russian 9K37 Buk was reported to have entered Chinese service in 2011 and is being deployed as a medium-range ‘gap-filler’ between the HQ-9 and shorter-range systems.

India

India continues work on various indigenous air defence missiles including the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO)/Bharat Electronics Limited Akash, a medium-range mobile SAM system for the IAF and army. In January 2009 the decision was made to induct the Akash into IAF service, and an order was placed with prime contractor Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) for two squadrons of the system. Indian sources state that a squadron includes two firing units each with four launchers. In March 2009 the Tata Group received an order from the IAF for the provision of 16 Akash launchers, while BEL was contracted to provide the Akash’s Rajendra tracking and engagement radars. The total cost for the two squadrons was around $222.2 million. The Indian Army placed an order for the Akash in June 2010, and the system was declared operational in 2015. In early 2014 a new version of the Akash was tested, offering an improved capability against Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), and remains under development. In a similar class to the Akash is the 9K37 Buk, 250 examples of which have been delivered to the Indian Army.

After a February 2005 evaluation that included, among others, the MBDA VL (Vertical Launch) MICA (Missile d’Interception, de Combat et d’Autodéfense/Interception, Combat and Self-Defence Missile), India signed for the delivery of four Rafael Advanced Defence Systems Spyder SAM ensembles in September 2006, and trials of the weapon were completed in India by the end of 2007. In September 2008 a contract was signed for the delivery of 16-18 Spyder systems from 2010 to 2012, which may have now been delivered, although information to this effect is hard to come by. Meanwhile, the DRDO is also collaborating with Rafael and IAI on a new-generation Medium-Range Surface-to-Air Missile (MR-SAM) project, but this has suffered from significant delays. A $2-billion contract was signed by the Indian government and IAI in March 2009, covering development of the MR-SAM, which would involve a version of the IAI Barak-II missile known as Barak-8MR. Subsequently, it was revealed that development was being conducted along two separate lines involving the Barak-8MR with a range of 37.7nm (70km), and the Barak-8LR with a range of 80.9nm. Should the MR-SAM project reach production, this mobile system is intended to replace the Akash and the ageing S-125 Neva/Pechora SAM. In the meantime, India has upgraded a number of its 18 S-125 systems to Almaz-Antey’s Pechora-M standard, which has seen an extensive upgrade of the system’s missiles, including the addition of a laser and infrared target tracker to allow the missile to hunt its target without relying on updates from the S-125’s SNR-125 Low Blow tracking and engagement radar.

Bangladesh

Elsewhere in the subcontinent, Bangladesh has made recent efforts to advance its GBAD capability, which was previously reliant on Chinese-supplied short-range systems. In May 2010 it was reported that the 9K37 Buk-M1-2 had been ordered for the Bangladesh Air Force, although the delivery schedule remains uncertain. In 2011 reports emerged that Bangladesh had ordered the Aerospace Long March International (ALIT) LY-80 from China, with deliveries to begin in 2013. The LY-80 is the export version of the PRC’s HQ-16 (see above) similar to the 9K37 Buk-M1-2 which has an engagement altitude of circa 82021 feet/ft (25000 metres/m), suggesting that plans to acquire the Russian system may have been shelved.

DPRK

Beyond South Asia, the air defence of the DPRK is entrusted to a varied inventory of SAM systems in which obsolescent systems are complemented by recent deliveries of more advanced Chinese and Russian equipment. Long-range SAMs comprise the HQ-9 (or perhaps S-300), the missiles and associated radars which were first identified in October 2010. These are complemented by the older, fixed-site Almaz-Antey S-200 Angara, four batteries of which were delivered between 1987 and 1988. Numerically the most important SAM in DPRK service is the Soviet/Russian S-75 Dvina, delivered between 1966 and 1971. A reported 45 battalions remain operational, comprising 270 launchers. At least some of these are likely to be Chinese-made HQ-2B/F/J versions. A total of 32 launchers are available for the S-125 Pechora-M, armed with the 5V27 missile, delivered in the mid-1980s. The DPRK’s most modern GBAD equipment is represented by the 9K37 Buk which was delivered in 2006. Since this is the original version of the 9K37 Buk the delivery may well have involved second-hand systems provided by a former Soviet state.

Japan

Across the Sea of Japan, together with the Netherlands, Japan was the first international customer for the MIM-104F when Lockheed Martin received a $532-million contract for 156 missiles (including examples for the US Army) in January 2005. Japan’s MIM-104F systems were deployed from 2007 and are operated by the Japan Air Self-Defence Force. Licence production of the system is carried out locally by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) as part of a package that included 20 MIM-104F systems. Each system in Japanese service normally has five launchers, each with four missiles ready to fire. A further three MIM-104F systems were also delivered as a rapid expedient to provide defence against the DPRK’s Rodong-1/2 and BM-25 medium-range ballistic missiles.

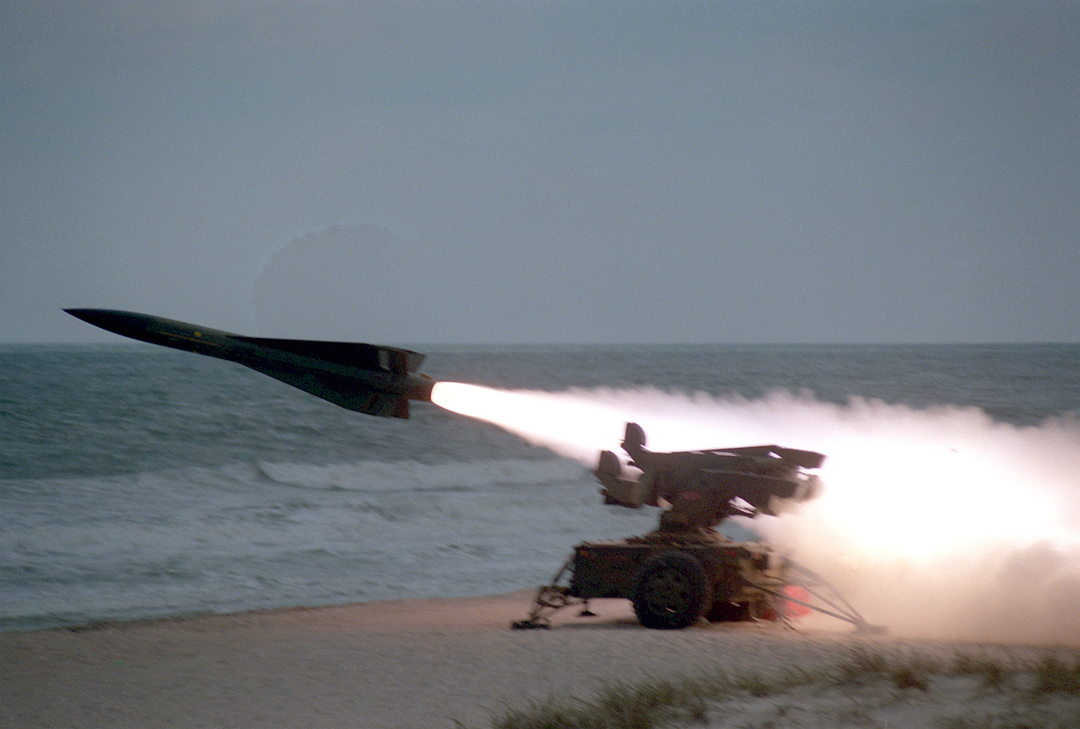

In addition to the MIM-104F, Japan operates the MIM-104C, the first of an eventual 47 systems being delivered in 1989, together with 980 MIM-104 missiles. Japan also employs the Raytheon MIM-23 Hawk SAM, the first examples of which were delivered in the early 1960s. Most of the systems acquired were assembled or manufactured in Japan. As well as 32 batteries and 1200 MIM-23A missiles, Japan received another 32 MIM-23B I-Hawk batteries from 1978, together with over 3200 MIM-23B missiles. Earlier systems were subsequently upgraded to the MIM-23B standard.

Pakistan

Back in South Asia, Pakistan has been linked with a possible purchase of the CASIC FT-2000/2000A, the export version of the PRC’s HQ-9 (see above), proposed as a counter to India’s deployment of Agni intercontinental ballistic missiles. Some sources indicated that Pakistan began to take delivery of two regiments (36 launchers) of FT-2000s in around 2011, but this has yet to be confirmed. Should Pakistan take delivery of the system it would mark a significant advance for Pakistan’s GBAD network, which previously relied upon the HQ-2 and HQ-2B for longer-range engagements. The single HQ-2 system was purchased in 1983 together with 40 missiles, and was joined by two battalions of improved HQ-2B systems (twelve launchers) delivered two years later. In 2014 it was reported that Pakistan had signed a $226-million deal for the supply of three batteries of the LY-80 system and its accompanying IBIS-150 radar. Delivery schedules have not been disclosed.

While the above systems are intended for defence of strategic objectives and are operated by the Pakistan Air Force, the Pakistan Army may operate a medium-range SAM in the form of 36 LY-60 systems delivered from the PRC between 1996 and 1997. However, some confusion exists as to whether these are intended for ground-based or naval applications. In 2007 an order was placed for the MBDA Spada 2000 system, an improved version of the Spada from which the LY-60 was derived, which have now been delivered.

Singapore

Like Pakistan’s rival India, Singapore has enhanced its GBAD capabilities with Israeli technology. In 2008 Singapore signed a contract for the Spyder-SR system (see above) to fulfil the GBAD requirements of the Singapore Armed Forces Air Defence Group, itself part of the Republic of Singapore Air Force. Deliveries of 20 systems began in 2010 and these are equipped to deploy not only the medium-range Rafael Derby missile but also the company’s short-range Python-5. A total of 75 examples of each missile type were procured. The Spyder-SR has been integrated with the existing medium- to high-level MIM-23B and short-range Saab RBS-70 SAM systems as part of the national air defence network. In 2013 Singapore unveiled plans to acquire the MBDA Aster-30 missile for the RSAF. This will extend the reach of the GBAD network and provide a BMD capability. It is not thought that these missiles have yet commenced delivery. Meanwhile, a single MIM-23B squadron of six systems was delivered in the early 1980s and was originally provided with 500 MIM-23B missiles. More information on Singaporean defence procurement can be found in Alex Calvo’s Survival Instinct article in this issue.

Taiwan

Taiwan’s multi-layered air defences are headed by the army-operated MIM-103F. In August 2009 the Taiwanese government agreed to the procurement of four (some reports suggest six) MIM-104F systems in a deal worth $3.2 billion, which included 264 MIM-104F missiles. Meanwhile, a separate $600-million contract with Raytheon covered the upgrade of three existing MIM-104C fire units to MIM-104F standard with the upgrade commencing in 2011. Indigenous SAMs include six battalions of Chungshan Institute of Science and Technology (CSIST) Tien Kung-I systems, and an undisclosed number of Tien Kung-II systems, while the latest Tien Kung-III began to be delivered in 2014. Taiwan continues to operate the MIM-23B, in the form of four battalions for 100 launchers delivered in 1977-1978, and a further five battalions delivered in 1981-1982. In late 2014 it was reported that this system would be retired by 2017 and replaced by Tien Kung-III (see above), giving a BMD capability.

The investment into GBAD systems highlighted in this article in the Asia-Pacific region is unlikely to reduce in the coming years. According to Sebastian Sobolev, deputy director at Avascent, a Washington-DC based consultancy, “setting (orders for the MIM-104 SAM family) aside investment in air and missile defence spending in the Asia-Pacific generally amounts to roughly $4.2 billion per year, and is anticipated to grow at nearly nine percent annually through to 2020, a slightly faster rate than defence procurement in general, which may suggest that this is a highly prized capability.” Continuing ballistic missile proliferation in the DPRK, not to mention the procurement, of advanced 4.5- and fifth-generation fighter aircraft is likely to continue to motivate such spending patterns in the coming years.